Gary Nelson, AIA, is an architect for the City of Phoenix, responsible for projects such as the renovation of Talking Stick Resort Arena. Working for other firms, he’s been involved in projects like the original design for Chase Field (then known as Bank One Ballpark), the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta and civic work for the City of Glendale. Yet as an African American, his path to success has not always been easy.

“When I enrolled in architecture school in Chicago in 1977, there were 14 of us in the program who were African American,” Nelson recalls. “All of us were told by professors and advisors that we should change our majors. After two years in the program, I was the only African American left.” As he climbed the career ladder, there were other slights, small as well as significant. “I was usually the ‘only lonely,’ the only person of color on a design team.”

Carlos Murrieta, AIA, had some similar experiences. Educated in Mexico, he came to Arizona in 2001 with the idea of doing some cross-border projects, but decided to stay after joining a local firm. Despite career success, including launching his own firm, Merge Architectural Group, and winning AIA Arizona’s Young Architect Award, Murrieta, too, felt the slights of racism. “I always felt like I was the guy on the side,” Murrieta explains. “Not being from the U.S. created a sense of separation. Sometimes, I’d be the only Latino in the room, and people would walk away from me.”

Nelson decided to do something to address the issues faced by minorities in design/build professions. In 2017, he founded the Arizona chapter of the National Organization of Minority Architects, or NOMA (nomaarizona.org), with 16 other members. Murrieta currently serves as president.

“NOMA was founded in 1971 by 12 African American architects who had attended the national AIA conference in Detroit,” Nelson explains. “They wanted an organization that was inclusive and actively promoted increasing the number of African Americans in the profession and increasing the number of students of color who studied architecture.”

According to Nelson, only two percent of registered architects today in the U.S. are Black—and only .4 percent of registered architects who are Black women, giving NOMA a clear mission. “Arizona’s first African American registered architect was Rushia Fellows, and that only happened in the 1960s,” he points out.

Today, NOMA Arizona has about 67 members, Murietta says. “We encourage diversity, both in gender and race, as well as in profession. It’s not just architects—we have contractors, engineers, interior designers and others in the group.”

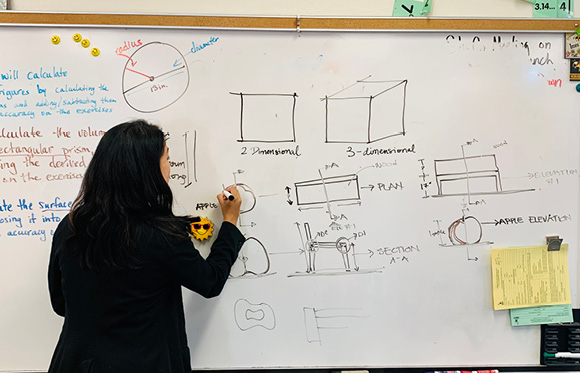

“While AIA supports the profession,” Murietta continues, “NOMA supports the community as well as the profession.” He points out scholarships, tutoring and mentoring as part of the organization’s concerted efforts to put forth the idea of architecture as a profession to minority students. Following the “see it, be it” philosophy, Murietta says NOMA members volunteer in schools located in underserved communities for career days or support programs. With the pandemic, the group is also working on an eight-week virtual program for teachers who request it, emphasizing drawing and design. The group also mentors members who are seeking professional registration. Another recent community service program was the design of a tiny home for the City of Phoenix, which the city is currently reviewing for permitting. “The plans would be free to anyone who wants to build this kind of house,” he explains.

After the George Floyd murder last year, the chapter organized a special meeting and came up with a ten-point call to action in response. “We had almost 100 people on the video call,” Nelson says. “For the first time in my career, others really wanted to know the problems and how to address them. The ten points are not about special treatment—they are about respect and listening. This is a tough conversation, but one that needs to happen everywhere, including our profession.”

Among the ten points that NOMA Arizona distilled are acknowledging historic and current systemic and institutional racism and gender inequality in the United States, encouraging firms and individual to mentor all staff who have expressed an interest in “next levels,” eliminating subjective promotions and partnerships, and a zero tolerance for racial, sexual, LGBTQ and religious disrespect and harassment.

This year, the group is continuing its largely virtual meetings and several hands-on projects. The pandemic has hardly slowed things down. “I would like to see a day when an organization like this isn’t necessary, when minorities are fully part of the profession,” Nelson reflects. “But until things change, the need is necessary.”